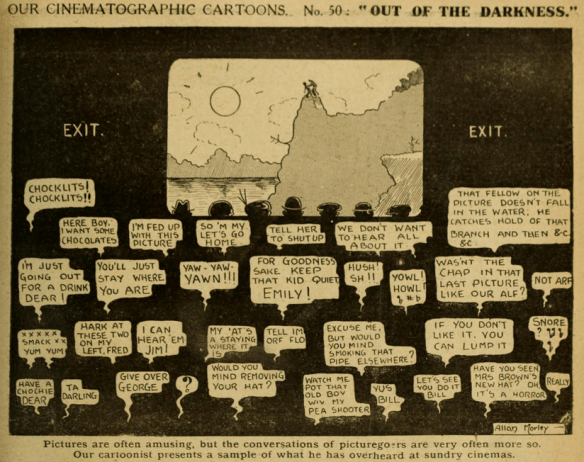

Voices filling the dark; Pictures and the Picturegoer 19 Feb. 1916: 475.

At the end of January 1916, cinema-trade-journal Bioscope’s Irish correspondent Paddy congratulated George Hay, manager of Waterford’s Broad Street Cinema, on his catchy new programmes. “‘The Picture and Picturegoer’ is on sale in the theatre,” he observed, “and Mr. Hay has had his entire programme printed on the front page. This catches the public eye, and moreover, when the paper is left lying about at home it catches the eye of other members of the family.” Getting and remaining in the public eye was important to the cinema business, but much of the publicity it garnered in Ireland in February 1916 was negative.

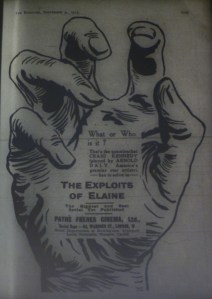

Eye-catching ad for The Exploits of Elaine incorporating the clutchching hand motif; Bioscope 9 Sep. 1915: 1127.

Cinema’s “Clutching Hand” certainly caught the public’s eye in February 1916. The Exploits of Elaine (US: Wharton, 1914) serial had been showing in many Irish picture houses, including Dublin’s Rotunda, which had shown the first episode, “The Clutching Hand,” on 18 October 1915. The plucky Elaine’s (Pearl White’s) repeated imperilling by master criminal the Clutching Hand (Sheldon Lewis) and rescuing by scientific detective Craig Kennedy (Arnold Daly) proved a lucrative formula. Showing one episode a week, the Rotunda reached the 14th and final episode, “The Reckoning,” on 20 January 1916. “Those who have followed the various episodes in this serial picture must not omit to visit the Rotunda,” a newspaper article warned, “and witness the first dénouement of the Clutching Hand, in which the culprit is revealed through his inadvertence in referring to the hidden treasure” (“The ‘Clutching Hand’ Revealed”). “Thus far,” the Irish Independent observed, “‘Exploits’ may claim to have established a record in general interest, and increased attendances are like to be experienced as the story reaches its climax” (“Dublin and District”).

Poster for the episode of The Exploits of Elaine in which the Clutching Hand’s identity is revealed. Source: Wikipedia.

Other picture houses were not far behind the Rotunda. On 10-12 February, Cork’s Coliseum showed the 13th episode, “The Devil Worshippers,” in which the identity of the master criminal the Clutching Hand is revealed. Smaller towns started the serial later, with the first episode being offered to audiences in Ballina in June 1916 and in Longford town in July 1916. Seeing its success, producers Wharton Studios had quickly followed it with The New Exploits of Elaine (US: Wharton, 1915), and the Rotunda and others would begin showing this as soon as the original concluded. As a result, the phrase “Clutching Hand” was in circulation in Ireland as a synonym for criminality throughout 1916. Calling for an enquiry into the military killing of civilians during the Easter Rising, for example, Dublin alderman Laurence O’Neill described himself as having “the clutching hand of the military authority upon him” (“Action of Corporation”).

We have seen here that White’s Elaine offered young women an adventurous role model, but court cases reveal that the Clutching Hand proved equally inspirational for the criminal careers of Irish child gangs. A writer in the Southern Star noted that “the Exploits of Elaine, or the Clutching Hand, is drawing crowded houses at the local Kinema” in Kinsale, Co. Cork. As a result, “[a]ll our youth are now budding Sherlock Holmes.” But the influence of the serial was not so clear cut:

This habit of observation properly cultivated is a very useful thing and fits the youngster for life’s battle, but, judging by the cases before the local court on Saturday last the Clutching Hand is also in evidence. A month was the reward in this case. (“Kinsale Notes and Notions.”)

Cinema could be educational by providing “useful lessons by ocular demonstration” but the “Clutching Hand remains.”

The Southern Star writer did not provide details of the case in Kinsale, but more evidence exists for those the Clutching Hand inspired in Newry and Mullingar. On 9 February 1916, seven boys and one girl were each sentenced to five years in various reformatories and industrial schools for stealing from shops in Newry. As each child was sentenced and put in a room beside the court, they sang the popular World War I song “Are We Downhearted? No!” – a song that begins by mentioning Pat Malone of the Irish Fusiliers – and cheered.“[A]s each fresh defendant came from the magistrates’ hands he was received with the sign of the ‘Clutching Hand,’ and solemnly responded” (“Boys and the ‘Clutching Hand’”). Sentenced to five years at Philipstown Reformatory for stealing 16s 7d and some handkerchiefs on 14 January, Bernard Hughes described how

they planned the robberies, and with the proceeds went to a picture palace, in the café of which they had tea, bread and butter, lemonade, chocolate, wine, and cigarettes. After sleeping in “Duck” Marron’s common lodginghouse all night at 4d. each, they visited Warrenpoint next day, where they were arrested.

The rich food and lodgings they experienced on their spree contrasted markedly to the conditions in which at least some of them lived. Head Constable Mara gave evidence of having been invited by accused James O’Hare’s father, a sailor home on leave, to see how his children were living:

They were covered with vermin, and their mother was drunk. The house was filthy, and nothing in it but a dirty sack for five children to sleep on. [Another accused John] Hanratty, it was stated, lived in the worst house in Newry, with his mother and his sister.

Such testimony does not appear to have influenced the magistrates towards any more leniency than extended incarceration. Nevertheless, the solidarity between the children in court seems remarkable. By mentioned just these signs of defiance in court without the details of their desperate living conditions, most papers presented the case as a commentary on the antisocial nature of cinema.

Reports of the Newry case, or similar cases elsewhere, may have inspired the behaviour of the 12-year-old John Connor, Thomas Keena and Michael Creevy who on 26 February 1916 were arrested for stealing in Mullingar. Sergeant Campbell informed the petty sessions that having been told by J. F. Gallagher that £1 10s had been robbed from his shop, he went to Healy’s Picture House and found the boys in possession of the remainder of the money. Although the chairman of the petty sessions seemed inclined to grant Creevy’s mother’s request for bail for her son, the boy himself asked not to be sent home but to go to a detention home with the other boys. While in the cells at the police barracks, the boys reportedly sang “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” and shouted “Hurrah for the Clutching Hand” (“Robbery in Patrick Street”). The magistrates hearing the boys’ case sent a resolution to the Mullingar Town Commissioners urging them not to renew picture house licences until the proprietors undertook not to show any film that depicted burglary to children under 16 (“Youths Charged with Robbery”). The Commissioners simplified this by barring boys under 16 from evening performances (“Mullingar Town Commissioners”).

These cases lent fuel to the campaigns to regulate – or eliminate – cinema. “What is really a little alarming,” argued a writer in the Irish Times citing the Newry case,

is the prospect of a gradual Americanisation – and a very cheap sort of Americanisation at that – of all our English and Irish ideals and of the whole British outlook on things in general. To-day the picture-house does little or nothing for patriotism; it is not helping us to victory in the field. (“American Films.”)

This writer supported H. G. Richards’ suggestion in the London Times that the importation of all foreign – mainly American – films be banned, including raw film stock. Richards argued this move would save £2 million, free up space on cargo ships, encourage the British film industry to expand, and make films more educational. Considering some of the economic and moral arguments for and against a ban, the Sunday Independent seemed to come down against it. “Naturally for the defence,” an editorial item observed, “we have the sound standing arguments of the public need of diversion in war as well as peace-time, and the benefit to temperance of the competition of the Cinema theatres with the publichouses.” The writer seemed to consider something of a clincher the fact “that on each of the British battle cruisers which await the appearance of the German fleet is installed a picture show for the amusement of the fighting men” (“The Passing Show”).

Few in the industry shared Richards’ views. Fan magazine Pictures and the Picturegoer pointed out that while British audiences were staunch supporters of British films, domestic companies could not supply the market. “[U]nfortunately, the [British] films that are worth much would not go far to feed the four thousand odd theatres,” s/he observed. “Indeed, if all the British film companies suddenly decided to work day and night in order to turn out films with the rapidity of a munitions factory, the output would provide but a mere drop in the ocean” (“Don’t Close Our Picture Theatres”). As the article pointed out, the dearth of people and materials in wartime made it unlikely that the British industry could expand to any great degree.

While these kind of arguments were unlikely to convince those intent on reshaping a mainly entertainment medium into a mainly educational one, other government priorities militated against a film-import ban. The Irish papers prepared their readers for the imposition of an amusement tax in the upcoming budget as a much-needed revenue-raising measure. Cinemagoers would feel the clutching hand of the war economy in May.

References

“Action of Corporation: Petition to House of Commons.” Freeman’s Journal 3 Aug. 1916: 7.

“American Films.” Irish Times 14 Feb. 1916: 4.

“Boys and the ‘Clutching Hand’: Remarkable Case at Newry.’” Irish Times 10 Feb. 1916: 6.

“The ‘Clutching Hand’ Revealed.” Irish Times 20 Jan. 1916: 9.

“Don’t Close Our Picture Theatres: ‘Movies’ the War-Time Medicine of the Masses.” Pictures and the Picturegoer 26 Feb. 1916: 494.

“Dublin and District: Rotunda Pictures.” Irish Independent 20 Jan. 1916: 5.

“Kinsale Notes and Notions.” Southern Star 5 Feb. 1916: 7.

“Mullingar Town Commissioners: Cinemas and the Youth.” Westmeath Examiner 18 Mar. 1916: 6.

Paddy. “Pictures in Ireland.” Bioscope 27 Jan. 1916: 344.

“The Passing Show.” Sunday Independent 13 Feb. 1916: 4.

“Robbery in Patrick Street: Extraordinary Performance of Boys.” Westmeath Examiner 4 Mar. 1916: 8.

“Youths Charged with Robbery: Cheering for the ‘Clutching Hand.’” Westmeath Examiner 18 Mar. 1916: 6.

Pingback: The Constant Watchfulness of Irish Cinema in March 1916 | Early Irish Cinema

Pingback: Irish Cinema and Population Control in November 1916 | Early Irish Cinema

Pingback: Cinematic Criminality in August 1918 | Early Irish Cinema