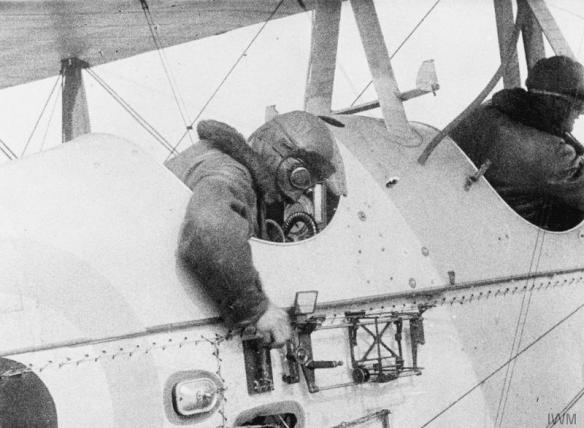

A range finder telegraphs the location of German positions in With Britain’s Monster Guns; Imperial War Museums.

Many people experienced the British Army’s Somme offensive, which began on 1 July 1916, as a cinema picture. Not for the first time, cinema took its place among the print media in eliciting support from the British and Irish populations. Irish newspapers reported how this happened in London. “London was in a state of great excitement yesterday afternoon and evening on the news from France,” the Irish Times’ London correspondent reported.

It was just after one o’clock when the evening papers came out with the news, and Fleet street was quickly alive. The papers seemed to seen in thousands, and anybody’s paper was public property, for if a person stopped to read the news he was a once surrounded by people who also wanted to read it as well.

However, not every Londoner learned the news from the press: “The news quickly spread to the West End, and lively scenes were witnessed in some of the restaurants. At the Coliseum the news, flashed on the cinema screen, set the house cheering with enthusiasm, a group of wounded men leading off” (“London Correspondence,” Times). According to the Freeman’s Journal’s London reporter, it was not just in the Coliseum that this occurred. “In some of the cinema theatres the management rose to the occasion by flashing the text of the communiqués on the screen,” s/he observed, “and the audiences cheered lustily as the welcome words appeared” (“London Correspondence,” Freeman).

The Cork Examiner reported that picture houses were also responsible for such manifestations of popular enthusiasm in America, which had not yet entered the war. “General Haig’s late despatch from headquarters announcing the capture of German trenches and various villages,” the report read, “arrived here between nine and ten o’clock last night, and at many of the cinema palaces was thrown upon the screen and cheered by crowds” (“American News”). In this way, cinema extended the propaganda function of the press into the largely entertainment spaces of the picture houses, in both the British capital and in a neutral but assumed friendly country.

Soldiers at the Somme used cinema – a sometimes overwhelming spectacle – to describe their experiences of war. The explosion of a mine at Beaumont-Hamel featured in many accounts, including that of an unnamed sergeant who “with great glee” and “unusual power of description, said it reminded him of the pictures you sometimes see in cinemas of petroleum stores blowing up – always in America.” This soldier’s descriptive powers were unusually bound up with cinema:

“I’d been in that part of the line for some time,” he said, “and, Lord, how we used to curse that mine. Fatigue parties always were wanted to carry the stuff out, and then later on to take in the explosives. The exploding chamber was as big as a picture palace (the sergeant’s mind seemed to run on the cinemas that morning) and the long gallery was an awful length.” (“Advance in West.”)

This sergeant was not the only soldier whose imagination was fired by cinema. Fund-raising in Ireland ensured that Irish soldiers in France could also spend their leisure time watching films. In early July, the half-yearly meeting of the Cork Branch of the Irish Women’s Association for providing comforts for prisoners of war and men of the Munster Fusiliers read a letter of acknowledgement from General Bickie, commander of the 16th (Irish) Division for the £100 they had sent towards providing a recreation hut and cinema show that would travel with the division (“Comforts for Munster Men”).

One of the monster guns in With Britain’s Monster Guns in Action (Britain: British Topical Committee for War Films, 1916); Imperial War Museums

One soldier – who unlike the unnamed sergeant was identified as Irish – made a strong link between war and cinema. In a letter that was published in the papers, Private W. Campbell of the Derry Volunteers recounted to a friend his experiences of the 1 July attack by the Ulster Division. “You should have seen our boys advancing, the Derry and the Tyrone Volunteers leading. It was a fine sight,” he wrote,

something you would see in a cinema – chaps falling beside you and you going on making for your objective, shrapnel bursting above you, and high explosive shells bursting around, and machine guns sweeping the ground. You would wonder how they were able to advance; but our boys got the length of the fourth line of the Huns’ trenches, but had to retire to the third line, as there was a danger of their being cut off. We took about 600 prisoners; they belonged to the Prussian Guards. (“Somme Battle.”)

The Duncairn Picture Theatre opens; Belfast News-Letter 1 Jul. 1916: 1.

The New York Cinema opens; Irish News 31 Jul. 1916: 1.

War film matinees at Dublin’s Theatre Royal. Evening Herald 17 Jul. 1916: 2.

The military tenor of the event was maintained by the engagement of the Faugh-a-Ballaghs, the band of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, which played a special selection of music at each performance. “War pictures hitherto were usually sandwiched between Charlie Chaplin and similar films,” the Early of Derby argued at the films’ launch. “I think it is rightly felt that this ought not to be.” He also pointed out that the young were not the only target audience: “One of the objects of these films is to show the people of this country what we are doing in France with their brothers, their father, their husbands and their sons” (“Latest New Official War Pictures”).

Overall, the cinema picture was increasingly a weapon of war in Ireland in July 1916.

References

“Advance in West: Soldiers’ Experiences.” Cork Examiner 10 Jul. 1916: 5.

“American News.” Cork Examiner 3 Jul. 1916: 8.

“Battle of the Somme: Ulster Division’s Heroism: A Striking Tribute.” Belfast News-Letter 5 Jul. 1916: 8.

“‘Britain’s Monster Guns in Action.’” Irish Times 18 Jul. 1916: 6.

“Comforts for Munster Men.” Cork Examiner 4 Jul. 1916: 8.

“Glory of Ulster: Message from Sir E. Carson.” Belfast News-Letter 7 Jul. 1916: 10.

“Latest New Official War Pictures.” Evening Herald 12 Jul. 1916: 3.

“London Correspondence.” Freeman’s Journal 3 Jul. 1916: 4.

“London Correspondence.” Irish Times 3 Jul. 1916: 4.

“New York Cinema.” Belfast News-Letter 1 Aug. 1916: 2.

“Official War Picture Matinees.” Dublin Evening Mail 15 Jul. 1916: 3.

“Opening of Duncairn Picture Theatre.” Irish News 4 Jul. 1916: 6.

“The Somme Battle: Ulster Division’s Share in the Fighting: Emulating Their Ancestors.” Belfast News-Letter 20 Jul. 1916: .

“Ulster’s Sacrifice: The Division in Action.” Belfast News-Letter 7 Jul. 1916: 10.

Pingback: Irish Audiences Watch “O’Neil of the Glen,” August 1916 | Early Irish Cinema

Pingback: Exhibiting Tanks to Irish Cinema Fans, February 1917 | Early Irish Cinema